“Everything was instant warfare”: An MSF doctor reflects on Sudan

7 May 2025

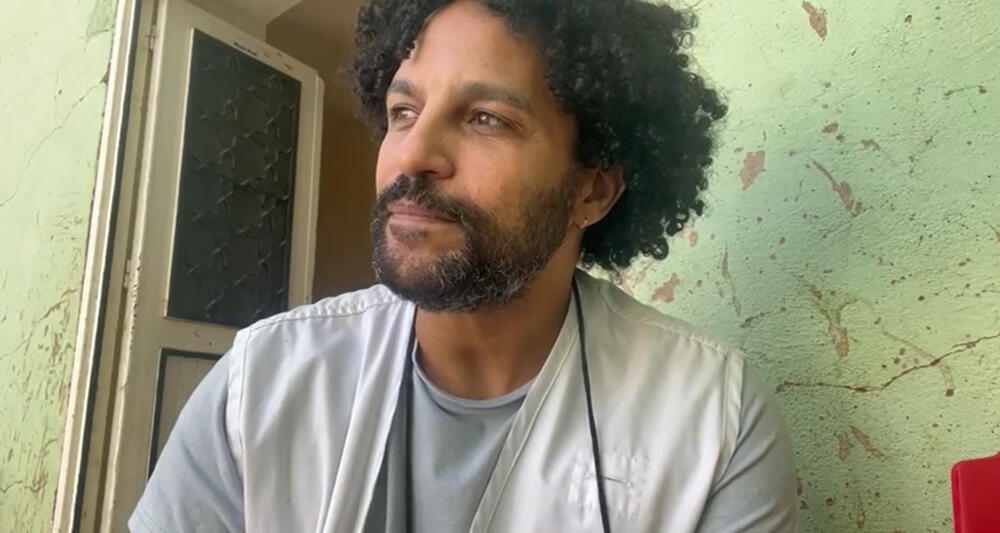

Dr Javid Abdelmoneim knew he had to say ‘yes’ when he got the call from MSF about going to Sudan just after war erupted two years ago. Half Sudanese and half Iranian, he was born in the UK and lived his first eight years in Sudan.

Though Javid had worked with MSF in emergencies around the world for 15 years, this assignment would be his most personal.

"In April 2023 I was in Malawi, working with the World Health Organization (WHO) in response to the cholera epidemic and Cyclone Freddy. Sitting at my desk one day, my phone lit up with a message from my cousin which simply said, "your dad’s safe". I didn’t know what he meant.

At the time, both my cousin and my dad were in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital. So I replied and then checked the news.

To my shock, I watched as videos showed war planes flying over the city and reports of the outbreak of war between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

Along with my dad, who likes to spend Ramadan in Sudan, many of my Sudanese family living in the diaspora were also back, together with my family who still lived in the country. They were all in Khartoum for the wedding of one of my cousins.

I hoped there would only be one day of fighting and then they'd stop. But what ensued was just the total the collapse of a nation.

The first assignment

Everything was instant warfare. Those first days of the war were harrowing. Everyone was in lockdown. My cousins had their house shelled. Thankfully, no one was killed.

Throughout my lifetime Sudan hasn’t been free of war, but it's never been in the city. It was shocking to see shelling and gunfire in all the streets of Khartoum.

Over the next week, the family organised five different convoys out of the city, but my dad very nearly missed the last one. We were all deeply stressed until the last convoy left the country. Only then, once my dad was out and safe, I felt relief.

That same day, about ten days after the war started, I got the call from MSF asking if I was available to go to Sudan. With my WHO contract ending imminently, I said yes.

The following week I was getting on a humanitarian flight into Port Sudan with the plan to go on to Omdurman, in the west bank of the River Nile, in Khartoum.

“As I was getting live reports about the streets which were being bombed, I knew them all – some were even in my neighbourhood” - Dr Javid Abdelmoneim | MSF medical team leader

Bureaucratic impediments prevented us from reaching the hospital in Omdurman where we wanted to start our project. Already four weeks into the war, it was the only functioning hospital in that region.

Despite having the correct permits, we were turned back at the last checkpoint outside the city. Our two Sudanese colleagues had to work alone under the shelling to start the project, and we were only able to support them remotely from Port Sudan.

It was the first time I had been so comprehensively blocked from doing my work. I felt the professional frustration of not being able to do my job as a medical humanitarian.

There was also the personal frustration. I’ve worked in different places for MSF, but as I was getting live reports about the streets which were being bombed, this was the first time the names were not abstract. I knew them all – some were even in my neighbourhood.

I returned home from Sudan burnt out.

The second assignment

The second time I went to Sudan with MSF was a year and a half later in winter 2024. The project in Omdurman had been successfully started almost exclusively by our Sudanese colleagues.

Perhaps selfishly, for a bit of closure, I wanted to go and work there.

When I arrived, I was able to travel to Omdurman as a Sudanese national. We usually have mixed teams at MSF, with both international and local staff. Here I was with a foot in both worlds. It was a huge privilege.

In Omdurman we were supporting three hospitals – Saudi Maternity, Albuluk Paediatric and Al Nao General Hospital, which provides trauma, surgical and emergency care – the only three functioning main hospitals at the time.

Our support included logistics, water and sanitation, medical supply, and fuel to help with generators and staff transport.

Outside of the hospitals we also supported the Ministry of Health with vaccination campaigns and cholera response.

Challenges

The main challenge was that we were in the middle of a conflict zone, in between two military forces shelling each other. It was so close you could hear the gunshots and the risk of stray bullets was very real.

While I was there one of the medical directors of Albuluk Hospital was shot by a stray bullet as he walked through the hospital. Thankfully, it wasn’t a life-changing injury.

In the emergency room in Al Nao Hospital, we only had three days without shelling victims and mass casualty incidents throughout January.

The bureaucratic impediments continued to be a major challenge too, and the systems of control enforced by the authorities were so dense that we had to hire extra staff just to manage them. It was a resource drain which affected everything, including medical supplies.

It meant patients with exploded limbs would be without plaster casts, painkillers or gauze. The teams were having to wash and reuse gauze to dress wounds, which is far from ideal.

Building a mass casualty plan

A core priority of MSF’s work in Al Nao was to support the hospital administration to build a mass casualty plan. Introducing this systems-level approach would really make a difference to save more lives by assigning responsibilities more clearly and bringing more clarity to the action each department needs to take.

Mass casualty events affect nearly all hospital departments including x-ray, outpatients, inpatients, and the operating theatre. It's not just the emergency room that needs to respond when there's an influx of wounded people. This complex system of different departments needs to pivot instantly from day-to-day work to mass casualty procedures.

We needed to produce a living document that we could learn and debrief from after each event, to make sure we could provide better care each time.

For example, my nursing colleagues noticed that during mass casualty events, patients weren’t getting the necessary painkillers, usually because of a lack of supply.

Even with this challenge, the nurses were able to make sure that the most severely injured patients were getting at least a half dose of injectable paracetamol, about a child's dose.

That's all there was, and it was better than nothing.

The family graveyard

Despite the challenges, when I was approaching the end of my second MSF assignment in Sudan, I felt glad I went and could make more of a difference. But there was one thing I still wanted to do.

My family graveyard is located about a mile and a half south of where we were living in Omdurman. On my last day in Sudan, I managed to visit.

When I got there I met the caretaker who knew many members of my family. He explained to me that the graveyard had been a no man's land between the two front lines earlier in the war. The SAF and RSF had been shelling from the high-rise buildings on either side.

Approaching my grandfather’s grave, I could see the wall of the walled garden had been completely destroyed. Over at my grandmother’s side of the cemetery the mausoleum roof had collapsed and all the trees had been chopped down, probably for firewood.

I was so worried that I would just see bones but thankfully, all the graves were intact.

While I was there, I could hear huge booms of fighting in Khartoum. Part of me thought perhaps I shouldn’t be here due to the insecurity, but seeing the graves was so important to me.

I thought about my entire family clan living around the world. There wasn't an Abdelmoneim left in Sudan except from me at that moment in the family graveyard.

I took photos and sent them to all my cousins, explaining the level of damage, but that the graves are intact. “The ancestors are okay,” I told them.

I hope for an end to the war in Sudan as soon as possible. My greatest wish is to spend next Eid in Khartoum with all my family."

Listen to Javid on Everyday Emergency: The MSF podcast

Welcome to Everyday Emergency, a podcast by Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) bringing you true stories from people on the frontline of humanitarian emergencies across the world.