HIV in DRC: Youth clubs bring change and hope

1 December 2025

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), more than 60 per cent of the population is under 20 – a large, energetic, and promising youth population, but one that is highly exposed to HIV. In 2024, 15,000 young people under 25 contracted the virus, including over 9,000 under 15, mainly due to the lack of effective mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) prevention programmes during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.

“Despite the progress made, the fight against HIV remains fraught with obstacles for this generation,” explains Dr Gisèle Mucinya, medical coordinator of the Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) HIV project in Kinshasa. “Beyond the shortcomings of PMTCT, paediatric treatment remains insufficient, and access to testing is still limited. Tests are not always available, voluntary screening often has to be paid for, and the law forbids minors from being tested without a parent or guardian. On top of that, there is a glaring lack of information, even in schools.”

As a result, too many young people still develop advanced forms of HIV/AIDS due to insufficient screening and delayed treatment. At the Kabinda Hospital Centre in Kinshasa – a healthcare facility specialising in HIV care – 489 patients receiving treatment are under 25, including 344 under 18.

“I found out I was HIV positive when I was 15,” says Raïssa, 22. “Very quickly, I was stigmatised and rejected, even by my family. I had lost so much weight that I was forbidden from attending celebrations or funerals. I stopped leaving my room. Everything around me fell apart, simply because of how others viewed me.”

Like Raïssa, many teenagers bear a double burden: the weight of the illness along with its stigma. This leads to isolation, discouragement and, too often, treatment abandonment – that is, stopping or interrupting the medication that keeps the virus under control – sometimes with fatal consequences.

Youth clubs: A simple, human and effective model

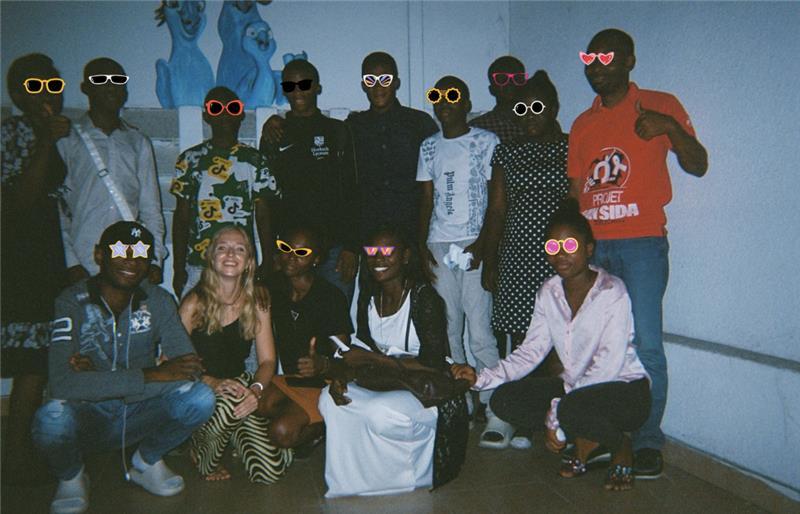

Treatment abandonment is a real concern among young people in Kinshasa. To address this, MSF and the Congolese association Jeunesse Espoir (“Youth Hope”) launched an innovative initiative in 2019: youth clubs. Their goal is simple: to offer adolescents and young adults living with HIV a safe, confidential and friendly space, linked to a formal healthcare structure where they can meet, share and support one another.

“It’s a model that works remarkably well,” says Dr Pulchérie Ditondo, head of MSF’s community-based medical activities in Kinshasa. “Members help, motivate and encourage each other. They become active players in their own health.”

Today, 83 young people aged 12 to 25 attend these clubs across four districts of Kinshasa. The initiative also includes an essential educational and preventive component: young people learn how to protect their health, understand their treatment and reduce transmission risks. The results are telling: in 2024, close to 80 per cent of them had a suppressed viral load – compared to 71% in 2019 - clear evidence of the model’s effectiveness.

More than just medical follow-up

The clubs go far beyond medical support. They are places for listening, learning and personal growth. Young people discuss their daily lives, doubts, relationships and dreams without taboos. They participate in educational sessions, creative workshops and discussions on sexual and reproductive health.

“For me, the club is like a big family,” says Kenny*, 22. “When I found out I was HIV-positive, I refused to believe it. Here, by talking to others, I learnt to accept my status. Today, I live without shame. I feel free and capable of anything. I’ve learnt to speak openly with my partner and no longer live in fear. I see the world in a positive light.”

The strength of the youth clubs also lies in their social impact. By helping young people break isolation and dismantle stigma, the model gradually transforms attitudes. Some members become facilitators or community advocates – raising awareness, encouraging testing and showing that with regular treatment, it is possible to live a full and healthy life. Others go further, acting as mediators to help address the social challenges faced within their communities.

A model to sustain and integrate

In 2024, MSF launched operational research to assess the effectiveness of this model in strengthening treatment adherence and improving participants’ overall health. The results are clear: The Youth Club model must be sustained and expanded.

“We have proof that it works,” insists Dr Ditondo. “This model keeps young people on treatment, prevents advanced forms of the disease – which are extremely costly to treat – and strengthens prevention throughout the community. There are plenty of reasons to support it.”

Despite its success, the future of this model depends on national and international funding for the HIV/AIDS response in the DRC. These resources remain structurally insufficient and have even declined since the US government reduced its international aid. The two main programmes – the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund – have both seen alarming cuts in their allocations to the DRC, with direct and long-term consequences for civil society initiatives.

For MSF, this financial strain makes it even more urgent for national authorities and international partners to support innovative, low-cost and effective initiatives such as Youth Clubs, and to integrate them into national HIV/AIDS strategies.

“We hope these clubs will exist across the country,” says Raïssa. “Wherever there are young people living with HIV, they must have this space if we want to reduce stigma and mortality. It can save lives.”

Restoring hope for a generation

Beyond statistics, the Youth Clubs embody a quiet revolution – that of a generation refusing fatalism and stigma, and is determined to take charge of its future.

They show that by investing in simple, community-based approaches centred on the real needs of young people, it is possible to transform the fight against HIV – not only in terms of health, but also in dignity and hope.

Every day, new faces emerge: young people regaining confidence, stepping out of the shadows and breaking the chains of silence and shame. Perhaps the key to the fight against HIV, in the DRC and beyond, lies right here – in the strength, solidarity and leadership of young people themselves.

MSF and HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS has killed more than 25 million people. HIV gradually weakens the body’s immune system, usually over a period of up to 10 years after infection. The virus was discovered in 1981.