Lomera, South Kivu: First came the gold rush, then the cholera

1 July 2025

In early May, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) launched an emergency response to a cholera outbreak in Lomera, South Kivu, where a gold rush and poor sanitation fuelled the rapid spread of the disease. Over 8,000 people were vaccinated and more than 600 patients received treatment, as teams worked around the clock to provide care and improve access to clean water.

Until recently, Lomera was a quiet lakeside village, barely known to most residents of South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. That changed overnight last December when gold was discovered in its hills.

The rush for fortune—intensified by economic insecurity caused by clashes between the M23/AFC armed group, the Congolese army (FARDC), and their Wazalendo militia allies—has turned Lomera into a magnet for thousands of people seeking work and safety.

In less than a year, the population exploded from 1,500 to more than 12,000. The village is now a sprawling chaos of mineshafts and makeshift shelters.

“We live in tough conditions without much space, but we put up with it because we need to earn a living,” said Chiza Blonza, 45, who left his farm in Walungu (some 90 kilometres away) behind to work the mines.

Every day, more people arrive, crowding into already packed shelters—sometimes 20 to a room. It was only a matter of time before disaster struck.

“Everything that could possibly fuel a cholera outbreak is here,” said Mathilde Cilley, MSF’ Project Medical Referent. “We’re seeing severe overcrowding, barely any clean water, open defecation on the hills, and a total lack of waste management.”

Cholera is endemic in this part of the DRC, and the lake is contaminated by the bacteria, but an epidemic of this scale is unusual. The first 13 cases in Lomera were reported on April 20. Within two weeks, that number soared by over 700% to 109 cases—a figure likely underestimated. Today, the town accounts for 95% of cholera cases in the Katana health zone, an area home to more than 275,000 people.

MSF was the main international organization to respond, launching a rapid emergency intervention on May 9. Teams worked around the clock to contain the epidemic. In just four days, MSF vaccinated more than 8,000 people—though limited supplies meant only single-dose regimens were administered, instead of the recommended two.

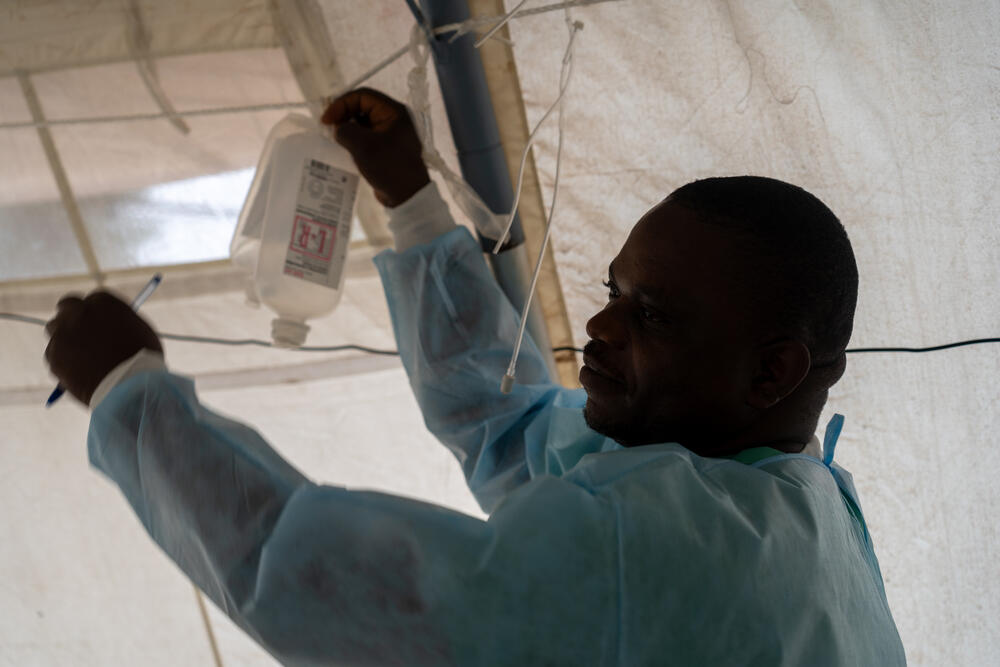

More than 600 people have been treated for cholera at a temporary 20-bed Cholera Treatment Unit set up by MSF, with many arriving in critical condition.

“The vast majority of our patients work in the mines, where they use contaminated lake water to separate gold from the earth, exposing themselves to the bacteria,” said Dr. Théophile Amani, an MSF doctor in Lomera. “Tough manual labour and high levels of alcohol consumption mean many are already dehydrated even prior to getting infected.”

After treatment, patients receive hygiene kits—buckets, water purification tablets, and soap—and vital health education from MSF staff on how to prevent future infections.

Bonheur Maganda, a 25-year-old originally from Kabamba, is among them. He came to work in the mines to provide for his children and said that many of his colleagues had also fallen ill.

“Without MSF, many of them would have died,” he said. “The health promotion officer explained the importance of washing my hands with clean water and being careful with food. I will share this advice with others.”

MSF also installed a lakeside water treatment facility and distribution point, delivering around 60,000 liters of clean water daily. One hundred latrines and twenty-five supervised handwashing points were set up across the settlement, including at restaurants and public gathering spots. Contact tracing and preventative treatment for those exposed to cholera have been crucial in containing the spread.

MSF’s emergency response will soon be handed over to other partners, but there is an urgent need for long-term solutions to guarantee continued access to clean water.

“Without significant investment in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure, outbreaks like this are likely to persist on a regular basis,” warns Muriel Boursier, MSF’s Head of Mission in Bukavu. “At present, the nearest well is three kilometres away. International partners and local authorities must step up and implement sustainable solutions.”

Given the constant flux of people moving in and out of the town, further vaccine supplies will also be necessary to protect the population.

“South Kivu—and eastern DRC as a whole—are facing major logistical hurdles in getting essential medical supplies, including vaccines, medicines, and equipment, to where they’re needed most,” said Muriel Boursier.

“While insecurity is a factor, the closure of airports in Bukavu and Goma has had an even greater impact, severely restricting our ability to deliver lifesaving aid. International cuts to humanitarian funding have also limited the availability of medical supplies. We urge governing authorities and international partners to do everything possible to help restore access and support the sanitary response to the wide range of health emergencies impacting the region.”

Responding to cholera outbreaks remains a central priority for MSF in the DRC. In 2024 alone, MSF teams treated more than 15,000 cholera cases nationwide, working alongside local health authorities and communities to save lives and stop the spread of disease.

Help us provide vital medical care to those who need it most.